Movement of the mandible typically involves bilateral action of the TMJs. Abnormal function in one joint naturally interferes with the function of the other. Depending on the osteokinematics, the arthrokinematics of the TMJ normally involve both rotation and translation. In general, during rotational movement the mandibular condyle rolls relative to the inferior surface of the disc, and during translational movement the mandibular condyle and disc slide essentially together.

The disc usually moves in the direction of the translating condyle.

PROTRUSION AND RETRUSION

During protrusion and retrusion the mandibular condyle and disc translate anteriorly and posteriorly, respectively, relative to the fossa (see Figure 11-13). The condyle and disc follow the downward slope of the articular eminence. The mandible slides slightly downward during protrusion and upward

during retrusion. The path of movement varies depending on

the degree of opening of the mouth.

LATERAL EXCURSION

Lateral excursion involves primarily a side-to-side translation of the condyle and disc within the fossa. Slight multiplanar rotations are typically combined with lateral excursion.55

Figure 11-14, B, shows an example of lateral excursion combined with slight horizontal plane rotation. The left condyle forms a pivot point within the fossa as the right condyle rotates slightly anteriorly and medially.

DEPRESSION AND ELEVATION

Opening and closing of the mouth occur by depression and elevation of the mandible, respectively. During these movements, each TMJ experiences a combination of rotation and translation among the mandibular condyle, articular disc, and fossa. No other joint in the body experiences such a large

proportion of translation and rotation. Because rotation and translation occur simultaneously, the axis of rotation is constantly moving. In the ideal case the movements within both TMJs result in a maximal range of mouth opening with a minimal stress placed on the articular surfaces.

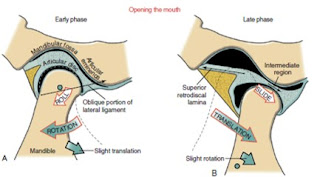

The arthrokinematics of opening the mouth are depicted for an early and a late phase in Figure 11-16. The early phase, constituting the first 35% to 50% of the range of motion,

involves primarily rotation of the mandible relative to the cranium.66,88 As depicted in Figure 11-16, A, the condyle rolls posteriorly within the concave inferior surface of the disc.

(The direction of the roll is described relative to the rotation

of a point on the ramus of the mandible.) The rolling motion swings the body of the mandible inferiorly and posteriorly.

The axis of rotation is not fixed but migrates within the vicinity of the condyles.24,60

The rolling motion of the condyle stretches the oblique portion of the lateral ligament. The increased tension in the ligament helps to initiate the late phase of the mouth’s opening.57,71

The late phase of opening the mouth consists of the final 50% to 65% of the total range of motion. This phase is marked by a gradual transition from primary rotation to primary translation. The transition can be readily appreciated by palpating the condyle of the mandible during the full opening of the mouth. During the translation the condyle and disc slide together in a forward and inferior direction

against the slope of the articular eminence (see Figure 11-16, B). At the end of opening, the axis of rotation shifts inferiorly. The exact point of the axis is difficult to define because it depends on the person’s unique rotation-to-translation ratio.

At the later phase of opening, the axis is usually below the neck of the mandible.24

The late phase of opening the mouth consists of the final 50% to 65% of the total range of motion. This phase is marked by a gradual transition from primary rotation to primary translation. The transition can be readily appreciated by palpating the condyle of the mandible during the full opening of the mouth. During the translation the condyle and disc slide together in a forward and inferior direction

against the slope of the articular eminence (see Figure 11-16, B). At the end of opening, the axis of rotation shifts inferiorly. The exact point of the axis is difficult to define because it depends on the person’s unique rotation-to-translation ratio.

At the later phase of opening, the axis is usually below the neck of the mandible.24

Full opening of the mouth maximally stretches and pulls the disc anteriorly. The extent of the forward translation (protrusion) is limited, in part, by tension in the stretched, elastic superior retrodiscal lamina. The intermediate region of the disc translates forward while remaining between the superior

aspect of the condyle and the articular eminence. This placement of the disc maximizes joint congruency and reduces intra-articular stress.

The arthrokinematics of closing the mouth occur in the reverse order of that described for opening.

When the mouth is fully opened and prepared to close, tension in the superior retrodiscal lamina starts to retract the disc, initiating the early translational phase of closing. The later phase is dominated

by rotation of the condyle within the concavity of the disc, terminated when contact is made between the upper and lower teeth.